To draw the world is to be in the world.

There is an immediacy to drawing and there is no end to drawing.[1] It is fed by a propulsive compulsion to put pencil to paper and be taken over completely. It is also an act of progression, for as soon as we place a mark onto paper, we register time. We create passages and we birth new entangled modes of being in the world because we always want to be more than one body.[2] Because we are, with Clarice Lispector, ‘afraid to be just one body’.3 And so we might recognise in Salman Toor’s drawings someone who is also afraid to be just one body, for he has always drawn bodies, bodies that are immediate and have no end.[4]

Half bodies and part bodies.

Bodies at rest or in play.

Bodies dressed up and painted.

Time-travelling wanderers that entangle themselves in new worlds.

And we might see how his paintings and drawings warmly illuminate these physical forms towards ‘a horizon imbued with potentiality’, as José Esteban Muñoz says.[5]

What are the poetic possibilities of an encounter with the border?

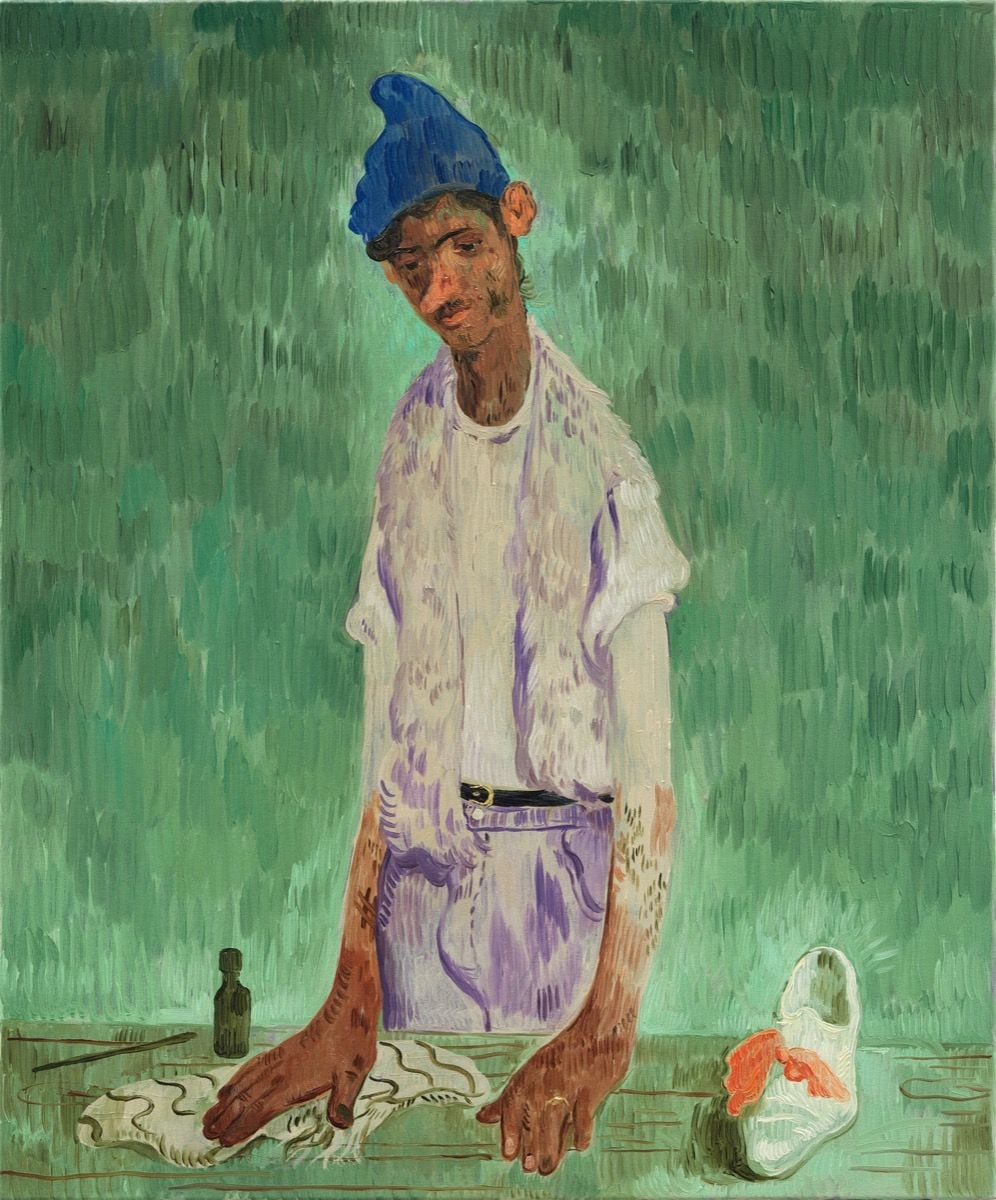

A border begins with a line, a line drawn by a hand that registers an inside and an outside: a potential. A line drawn by a hand that rests on, and registers, a table – a table to which Toor often returns, to separate us from the MAN WITH SCARF AND SHOE, 2020. Bodies become hypervisible when encountering

the intimacy of a border: the dividing line which inspects, categorises and then selects whose body is permitted to pass through this space. For Toor such works contain:

… both a sense of outer perception and an inner self-portrait. It’s about another threshold: that feeling I still have – coming from one part of the world into this, the English-speaking world, or Europe, or whatever – that those two things are sometimes at war with each other. I guess I want the viewer to become the immigration officer and decide who should be let in – and why.[6]

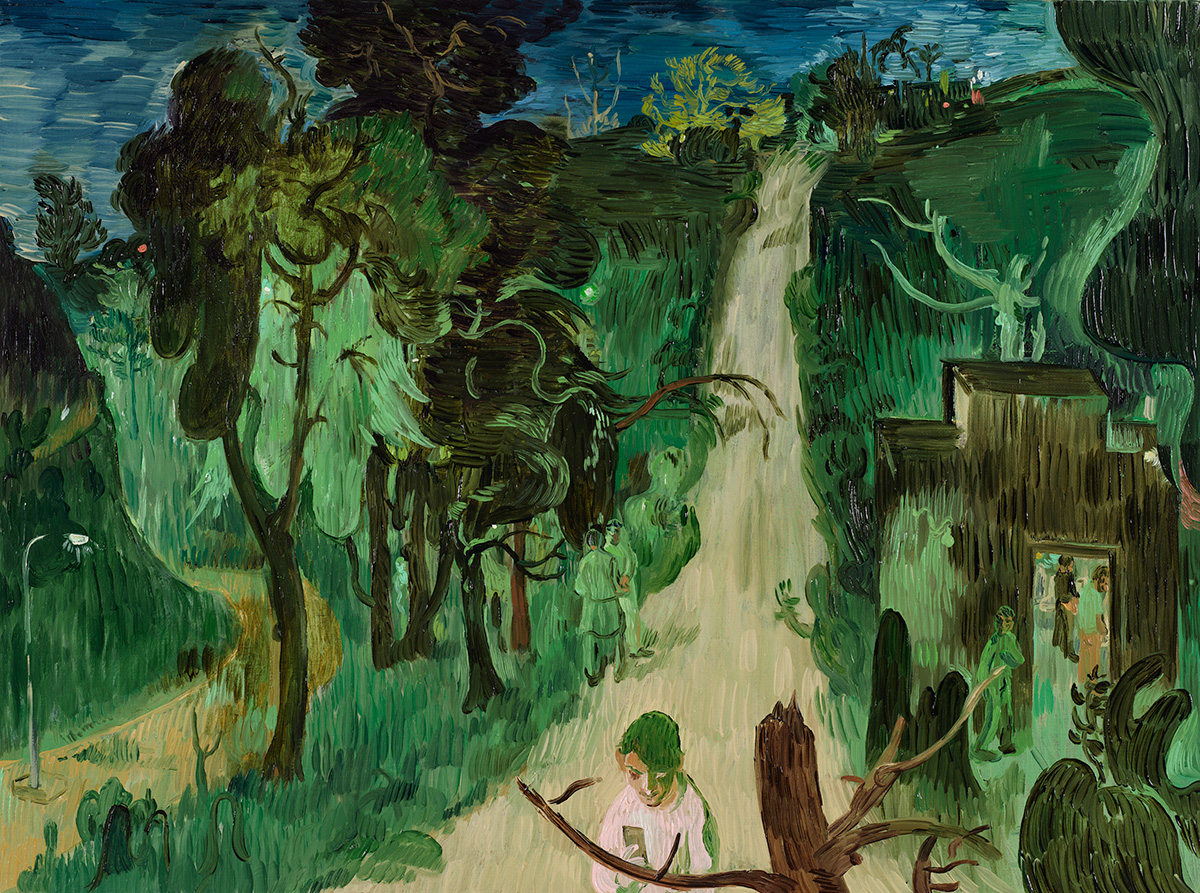

In Toor’s painting The Yellow Group (2022) and drawing Camera Group (2022) an assortment of people wait patiently at an airport security counter, forensically illuminated from below by a desk lamp. In Park Kissers (2022) a couple kisses in the park as a man watches from a public bathroom before abruptly departing; moments later in Twilight Park (2022) and Night Park (2022) a young man walks down the same path, absorbed in the screen of his smartphone, as the door to the bathroom hangs open and its occupants remain in view. These works convey pervasive questions around who is being watched and who is watching, who is cruising and who is policing.

These questions are their own kind of atmosphere; a generalised awareness that one is emmeshed within a network of glances. Such narratives pull our focus towards the social structures that guide behaviour – the phenomenon described by Foucault as ‘governmentality’ – and make visible the varying degrees of agency that we as individuals must have to transcend such forces.

A person reduced to a piece of paper.

A passive humiliation in the face of events that are beyond your control.

A conscious decision to lodge you in the position of a gatekeeper, where you can decide who gets to pass through a border.

Paradoxically, while the border is shown as a site of control, Toor’s characters acknowledge how we are also drawn to borders for the potential they rouse as sites of passage, exchange and transformation. Maybe he is always exploring containment. Maybe his characters think with Édouard Glissant, sharing his belief that:

We need to put an end to the idea of a border that defends and prevents. Borders must be permeable; they must not be weapons against migration or immigration processes.[7]

From this threshold, Toor’s narratives find connections with other gay, immigrant artists, like Danh Võ and Felix Gonzalez-Torres, who have similarly used their intimate lives to pose questions of what might constitute freedom. The answer, for Toor, might be a ‘leaky masculinity’, in which private desires both echo and infect the culture at large to produce a palpable emotional dissonance. This is most clearly felt in his museum paintings where his time-travelling, patch-worked protagonists register how these institutions have historically enabled systems of classification, that themselves have supported imperialism, colonial pillage and bureaucratic violence, amongst much else. And so, it’s no wonder there’s the cold spectre of death both animating and shrouding these images. At the very same time, there’s a warmly utopic impulse of potentiality. Again, echo and infection.

How am I going to move into a space?

Toor’s paintings and drawings emote a state of continual apprehension around zones of intimacy being crossed – be they personal and introspective, or public and social. These lines are spatially and symbolically created by Toor through the interplay of light, composition and colour, and the presence of recurrent motifs in the form of sidewalks and cars, doorways and windows, arrivals and departures, and the always present threshold of skin. It is wanting somebody to hold my hand, and at the same time not needing to be held in this strong singular sense. This anticipatory gesture tells us something about how Toor’s dissolution of form unfolds in relation to the limiting structure of the border.

The boundary between Ali’s face and the background onto which he is painted. A haloed face and the darkness around it. The couple you’re a little too close to and pushing in on. How a park is laid out in terms of the light. Or the way in which a bedroom window filters the New York City skyline.

The surface is the limit that causes the desire. By being pulled towards and pushing out at this limit, Toor activates and agitates the surfaces of his paintings; his colours spill out so that nothing is contained nor distinct. By marking a continual play between inside-outside within and across his images, Toor deconstructs any notion of a universal type of passage, making visible how this structure is constantly negotiated in its particularity, case by case.

Every potential lover can be a threat.

Every freedom holds the potential for domination.

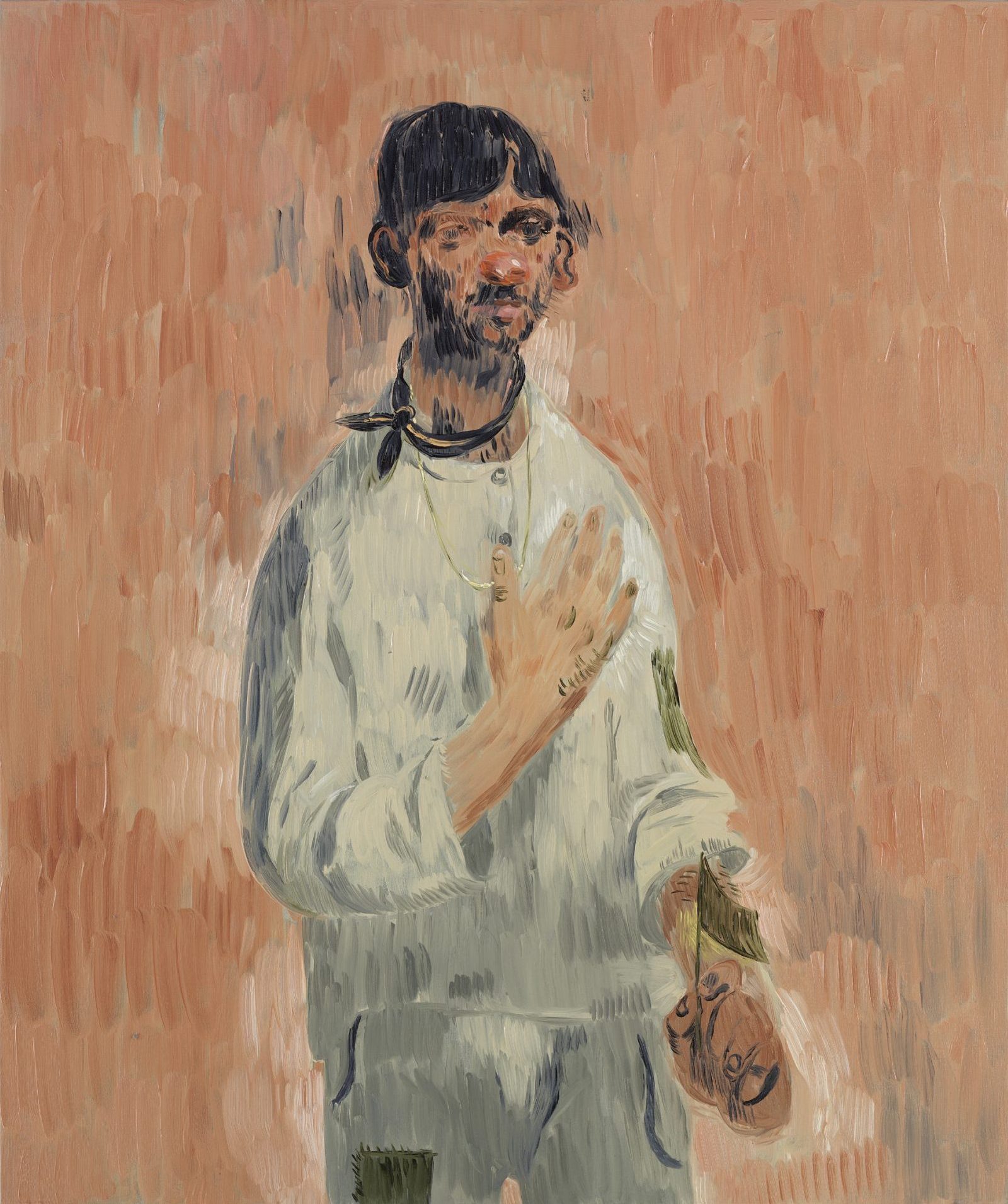

These questions, this apprehension, keep the pictorial tension constant so that the image doesn’t get lost in gooiness. So, while you register the heads Toor depicts as portraits, as slight likenesses, they are always in a stage of pre-dissolution even as they hold their own specific form. They are tremulous – is crossing this threshold going to fuck me up or release me? – yet always coherent.

Toor’s bodies dissolve and blur into other bodies.

In his painting The Doodler (2022) a young boy is sprawled out on a bedroom floor. His gaze is directed downwards as he guides the pencil across the page. It’s a yellowish-brown page tinted the same colour as this young boy’s hands, the same colour as his body. His hands press down onto the page as the drawing becomes the rest of him, it is another body. As queer theorist Leo Bersani might suggest: here lies their strength and their repose. By embodying the difference which is found in other subjects – be it personal, national, racial – Toor’s queer Brown boys are able to propose ‘a nonviolent relation to the world that doesn’t seek to exterminate difference’.[8] Rather, they propose solidarity through the arrangement of bodies drawn from different places, periods and styles that are collapsed together in pictorial space. They are home to a heady mix of intellectuals, artists and aesthetes often ‘theatrically’ dressed in a style akin to Cecil Beaton’s 1920s photographs of the Bright Young Things. And in a manner akin to Beaton’s outlandish entourage, there is a surplus of self-enjoyment that is reflected in Toor’s Wandering Beggars (2022), posing artists, and late-night flâneurs.

Toor draws parts of himself and mixes them with other past, present and future selves in such a way that ‘context becomes its own parade: the what I am here, the what I become over there’ – a form of ‘identity drag’ that invokes unrespectable lightness amidst the heaviness of race, history and gender.[9] With both heaviness and lightness Toor’s characters become all the more real and truthful. At the same time, his works acknowledge that to be visibly queer allows for both liberation and domination, and so his characters perform their queerness under a ‘cover of darkness’. They inhabit a nocturnal world bathed by the soft glow of candles, smartphones, lamps and streetlights within which ambiguous relationships are in quizzical play. With their limp wrists and frivolous demeanours, Toor’s queer Brown boys betray respectability and the standards imposed onto some, but certainly not all, bodies.

In many of Toor’s paintings the masculine is dispersed, broken down and held more lightly; experiences, people and ideas continuously rub over and slide past one another. In this increasingly viscous and amorphous pictorial space it is often uncertain where each body begins and ends.

Male torsos registered in languid lines and looping forms that neither enclose nor contain. Male faces whose speckled flesh falls away towards the edges. Soggy masculinity working against the phobia of contamination. Sissies moving away from the archetype of the disciplined hardy body as an articulation of queer identity and desire.[10]

In a celebratory spirit, Toor chooses to draw frail boys; boys in bed or by the window; lazy boys with cake who are delightfully soft, yet exuberant in a manner that recalls the camp performance of Richard Simmons. Everything and everyone stays flaccid. Nothing rises. Self-management that oddly never works. These are not the male bodies we typically consume.

Toor paints the lifter and elevates the sissy.

Sissy boys are agential.

They are frail but do not pine.

They are not an object of ridicule or diminution.

Sissy boys that pull apart the consumption of masculinity as smooth, sculpted, and still … as the alabaster surfaces of Neoclassical sculpture, the ultra-sleek photographs of Tom Bianchi, the bulging musculature of Tom of Finland, the loveliness of Luca Guadagnino’s Call Me by Your Name (2017), or the chiselled torsos circulated via social media and online dating apps.

Toor’s hairy Brown bodies muddy the discourse of gay male identity. His ‘fag puddles’ are joyfully leaky assemblages that reorientate us in history. As Mark Booth wrote in Camp (1983), ‘Camp takes styles from the past and uses them to sidestep the onward march of history’, and in doing so, reduces the historical to ephemerality.[11] The generative twist in Toor’s ‘puddling’ of the historical is that he encourages a continual re-narrativising of the past in the present, and the present in the past. His tumbling piles of disparate objects and disembodied body parts are brought together to create an unsettling temporal sculpture upon which branches sprout, flags are planted and candles glow. Through the impossibly curvy contortions and human-object entanglements that Toor assembles within his images he recreates himself in a manner that muddies the distinctions between personal biographical narratives, cultural influences and overarching histories. His ‘fag puddles’ slough off the inextricabilities of accepted identities in order to see his story, and other people’s stories, as a container of history without direction.[12] In this manner, Toor’s paintings and drawings recall Võ’s sculptural practice of physically dismembering and spatially dispersing static objects to create new hybrid forms that attempt to make sense of one’s own history. As Gonzales-Torres reminds us:

When we think of who we are, we usually think of a unified subject. In the present. An inimitable entity … We are not what we think we are, but rather a compilation of texts. A compilation of histories, past, present and future, always, always shifting, adding, subtracting, gaining.[13]

To be a unified subject and have a single body is to anxiously limit oneself from the fulfillment to be found in exchange with another person. The work of Toor, like Gonzales-Torres and Võ, is a compilation of ‘things’ that mixes historical traditions with pieces of local history, popular culture, politics and his lived experience. It is through this mixing that Toor dismembers his story to reassemble a self that resembles a past, while leaking outwards in all directions. In doing so, he signals an aesthetic change that sustains and enacts an epistemological change as he pulls from art history’s ‘pile of limbs’ to bring into being new bodies composed from part-bodies. After all, style is embodied knowledge and by specifically recounting the tradition of European painting in his compositions, Toor carries that history into this century and muddies the divisions of time, place and circumstance. He shows us that what painting can do as a progressive practice is to make history spatial as it becomes outer and inner, leaking in all directions.

- ‘There is no end to writing or drawing. Being born doesn’t end. Drawing is a being born. Drawing is born.’ Hélène Cixous, ‘Without end, no, State of drawingness, no, rather: The Executioner’s taking off’, in Stigmata, trans. Catherine A.F. MacGillivray, Routledge, Oxon, 2005, p 26.

- ‘The time involved of discharging a mark (the time of making); the way that each painting enters into a dialogue with painting’s long history (its intertextual appearance or temporality); the registration in painting of a passage from one figure to another (a migration from object (mark) to subject (god).’ David Joselit, ‘Timing Painting, Revising History’, Garage Museum of Contemporary Art, YouTube, 13 November 2019, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rIRW__JWkac.

- ‘I want somebody to hold my hand (in Brazilian: Papa the time I was hurt). I don’t want to be a single body. I am out of the rest of me, the rest of me is my mother, it is another body. To have a single body surrounded by isolation, it makes such a limited body. I feel anxiety, I am afraid to be just one body. My fear and my anxiety is of being one body.’ Clarice Lispector quoted in Hélène Cixous, ‘What is it o’clock? Or The door (we never enter) ’, in Stigmata, trans. Catherine A.F. MacGillivray, 97.

- ‘From the age of five, he drew constantly. His favourite subjects, borrowed from his mother’s fashion magazines, were pretty young women with flowing hair. “My aunt encouraged me to draw sports cars instead, so I drew a boxy, badly imagined vehicle with a girl’s heading sticking out the window”’. Calvin Tomkins, ‘How Salman Toor Left the Old Masters Behind’, The New Yorker, 8 August 2022 issue, p 3.

- ‘We may never touch queerness, but we can feel it as the warm illumination of a horizon imbued with potentiality.’ José Esteban Muñoz, ‘Introduction: Feeling Utopia,’ in Cruising Utopia, New York University Press, New York, 2019, p 1.

- Louis Wise, ‘How Salman Toor Became the Art Name to Know’, HTSI | Financial Times, 21 February 2023, https://www.ft.com/content/7c044487-eae8-4e6b-bb65-4761620371de.

- Édouard Glissant: One World in Relation, dir. Manthia Diawara, French with English subtitles, 48 minutes, K’a Yéléma Productions, 2009.

- Leo Bersani, Gay Betrayals, AfterAll Books, London, 2022, p 14.

- Travis Jeppesen, ‘Queer Abstraction (Or How to Be a Pervert with No Body). Some Notes Toward a Probability’, Mousse Magazine, 16 January 2019, https://www.moussemagazine.it/magazine/queer-abstraction-travis-jeppesen-2019/

- ‘When I was starting to form a path with my work, the male torso was accepted as synonymous with gay male identity or desire, and later, with the beginnings of an articulation of queer identity. I wanted to work away from this somehow, beyond the pictorial, which is why I focused on specific physical locations, spatial zones, and their power distributions, as a way of complicating that discourse.’ Tom Burr in ‘Tom Burr by Alan Ruiz’, BOMB Magazine, 15 December 2015, https://bombmagazine.org/articles/tom-burr/.

- Mark Booth, Camp, Quartet Books, London, 1983, pp 143–44.

- ‘I don’t really believe in my own story, not as a singular thing anyway. It weaves in and out of other people’s private stories of local history and geopolitical history. I see myself, like any other person, as a container that has inherited these infinite traces of history without inheriting any direction. I try to compensate for this, I’m trying to make sense of it and give it a direction for myself.’ Danh Võ quoted in Francesca Pagliuca, ‘No Way Out. An Interview with Danh Võ,’ Mousse Magazine, 1 February 2009, https://www.moussemagazine.it/magazine/danh-vo-francesca-pagliuca-2008/.

- Felix Gonzalez-Torres quoted in Elena Filipovic and Andrea Rosen, ‘Specific Objects Without Specific Form’, Felix Gonzalez-Torres: Specific Objects Without Specific Form, Koenig Books, London 2016, p 11.

- ‘So much of the art history that I love is a pile of limbs. There’s a poetry to seeing parts of bodies next to each other, in ways they wouldn’t be if they were joined together.’ Salman Toor quoted in Ambika Trasi, ‘The Self as Cipher: Salman Toor’s Narrative Paintings’, Whitney Museum of American Art, n.d., https://whitney.org/essays/salman-toor-self-as-cipher.